you dress too literally

part i of a series on personal style

The most common mistake I see people make when trying to expand their personal style is that they dress too literally. What I mean by this is that their relationship to inspiration is copy and paste instead of paraphrasing or taking notes. They see an aesthetic they like, maybe on pinterest or on the street, and rather than mulling over what drew them to the look, they recreate it exactly. They wear copied outfits like uniforms and blindly follow the rules that people share online for upgrading your aesthetic (like little top big pants, or don’t mix your belt and shoe colors, or add an unexpected shoe). The issue is not these rules or inspo outfits themselves, but rather the blind application of them to the self.

What makes fashion interesting is the relationship between a person and the items they are wearing within the context and culture they live in. What’s interesting on one person is not necessarily interesting on another, because what makes it interesting on their former is their unique intentionality in choosing each piece.

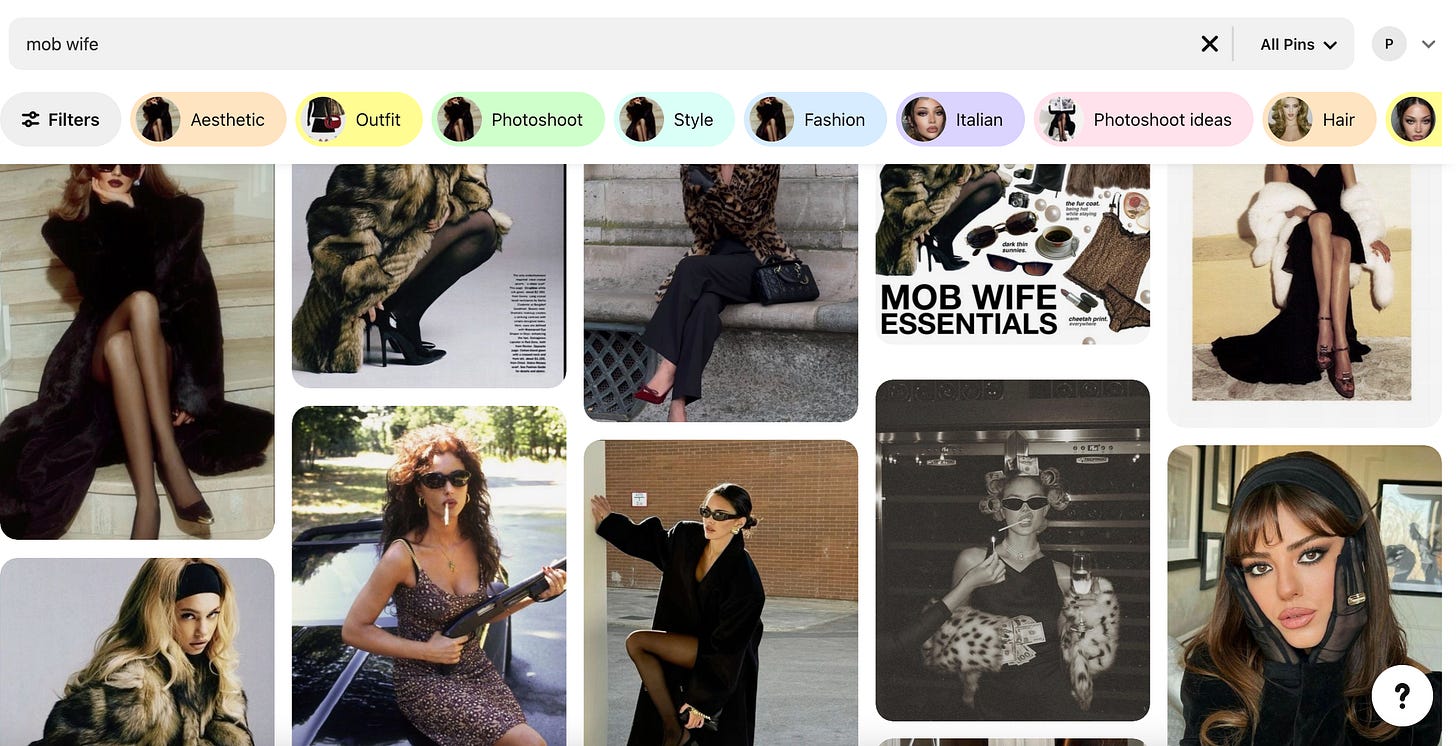

The classic example of dressing too literally is the proliferation of hyper-specific micro-trends and aesthetics, like mob wife or coquette girl or dark academia. Taking the first one, if you look at the pinterest page that comes up when searching by the phrase, the line between costume and outfit is blurred:

Pause for a second: what does it mean to dress like a mob wife? It doesn’t make any actual sense. I’ve never met a mob wife (though, presumably, if I have, and she’s good at what she does, I wouldn’t have known), but I can say with almost 100% certainty that she does not dress like any of the pictures shown above.

We have to think about this in relation to how we conceive of these aesthetics. Sticking with the mob wife example, I would guess that the dark colors, gauzy fabrics, cheetah print, oversized fur, etc., etc., are drawn from media portrayals of the mob wife. These images are gorgeous and alluring. So why don’t these looks work when recreated in real life? Filmic language (through costuming) does not have the same aims as personal style.

In film, while information is communicated multi-modally, it primarily relies visual cues. Dressing the mob wife character a certain way communicates specific information about her and her relationship to the mob boss, the mob itself, the time period, the place, etc., etc. Costuming is allowed to be this literal, to so heavily draw on the stereotype of a person, as this obviousness lets other complexity emerge in the piece. Instead of spending time analyzing what a character’s role is, the viewer is immediately clued in to who they are. An already coherent image of the character is given to them so that as the story unfolds, the viewer can easily adjust this image to account for the character’s development and arch.

Personal style, on the other hand, unfolds slowly over time, through the small decisions and circumstances of a person’s life. A real mob wife may share characteristics of what’s pictured above in her personal style, but only if it makes sense for her life. As she’s getting dressed, she’s not going to think: “I have to wear this fur coat so I look like a mob wife.” She’s just going to choose the fur coat because it’s her favorite, or it’s a blisteringly cold day, or she wants to show off her status. That specific moment choosing is why adhering to a specific aesthetic will almost always fail as a long-term means of improving your personal style: the sensibility of her look is not the same as the literality of what she is wearing.

Someone interested in the mob wife aesthetic might think they are drawn to specific facets of it, like the dark color palette or the cheetah print, but really, they are probably mostly drawn to some underlying energy that this aesthetic imbues. Maybe they want to feel more sultry. Maybe they want to embody a quiet confidence and power. Maybe they want to attract a specific romantic partner. Whatever it is, though, is (mostly) not embodied within the individual items of clothing that the fictionalized mobwife wears. Rather, the clothes are imbued with this feeling by being worn by the mob wife herself as she lives her life.

A good outfit, like a good lie, has a grain of truth in it. The way you dress can’t be divorced from yourself or your lifestyle, not if you want it to look natural and like you. By trying to adhere premade images to your embodied life, you walk around looking like you’re running late to a costume party.

If someone were to come to me wanting to dress like a mob wife, I would ask them what about the aesthetic draws them to it, and in what areas of their life they want to feel like this. Then I would look at the type of person they are and the everyday factors of their life, like work, hobbies, etc., and see how they can embody this sensibility in a way that makes sense for them.

I know these micro-trends and aesthetics arise for far more complex reasons than simply media consumption (like the algorithm and repackaging consumerism), but I think it’s important to make clear the relationship between aesthetic and functionality in fashion, as functionality is inherent to the art form. But more on all of that in the next parts…

Happy (kinda almost) New Year, my friends! 2024 was a banger and I have a gut feeling 2025 is going to be even better…